Not Qwhite Right

Part two of “Sounds About White.”

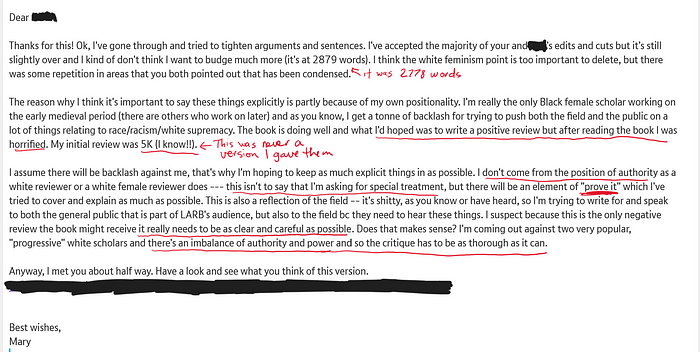

So there isn’t much to say about this other than this is where I met the editors on “most” of their edits and explained why I wanted a particular part in. The editors have attempted to paint this as that I didn’t accept “many, most, or the ‘vast majority’ of edits. Their edits were mostly crossing things out and not explaining what was wrong (until it became about one of the authors). Again, I’m showing you how the revised draft I sent them. I had thought I had cut it down to 2900+ but I had actually cut it down to 2700+. It was shorter, less instructive but the essence was there. To get it down, I had tightened up the language considerably (because instead of the editors suggesting that — they just cut huge portions). You can compare the 2 versions by going back to the previous version here.

Review of The Bright Ages

By Mary Rambaran-Olm*

The Bright Ages, written by historians of the European Middle Ages Matthew Gabriele and David Perry, takes readers on a journey starting with the 5th-century fall of Rome and ending with the 14th-century Italian poet Dante Alighieri. Gabriele and Perry invite readers into their work with “our story begins[,]” which is an interesting opening to a Black/Brown medievalist and public-facing scholar like myself. Texts that begin with the words ‘our story’ demand that we ask who is included among ‘us’? In my own pedagogy, I often ask myself and others to interrogate who ‘we’ and ‘our’ refer to in written discourse and conversations. This is a good way to identify a core audience. I wondered whether the authors were taking readers on a dramatized first-person historical tour of the Middle Ages, whether they were talking about ‘us’ as readers, or whether it was them as scholars.

Writing for a general (and possibly global) audience is a difficult task. I applaud Gabriele and Perry for assembling a collection that aims to challenge misrepresentations of the European Middle Ages and offer a messier, more intricate, and (in some ways) more diverse image of the period. But intentions are one thing and outcome is often another. Some of the book’s successes include the writing style. It’s accessible; the book’s prose is conversational and straightforward, devoid of dense academic jargon. For readers with no previous knowledge of some of the historical figures or stories, it might be confusing to keep track of names and dates, especially given the speed with which Gabriele and Perry move through events.

The Bright Ages wastes no time lingering on individual places, people, or events. The book weaves through time and areas across Europe in a straightforward way. The chapters are short and sweet. The visual theme underscored throughout is one of “light”: the authors play on sensory images with elaborate descriptions of colorful stained-glass windows, towering architecture, the warmth of a flame here or the feeling of sunlight there. This is further emphasized in the color pictures located near the middle of the book. All of these things make the structure and story-telling accessible.

Despite the images and the title, the language and core themes of the book don’t reveal brightness so much as ‘whiteness.’ What unfolded as I read through each chapter was not necessarily a revelation of a more complex European history but an understanding of who the authors thought was at the heart of “our” story. Gabriele and Perry describe how “scholars in medieval studies themselves [historically] sought a history for their new world order to justify and explain why whiteness — a modern idea, albeit with medieval roots — justified their domination of the world” (xiv). I was struck by how the book uses many terms geared towards a specific type of reader. The writing style and packaging seems to be at odds with the reader. What is ‘whiteness’ to them?

A definition of ‘whiteness’ is absent from The Bright Ages. The analysis and study of ‘whiteness’ is anchored in the work of French West-Indian psychologist and philosopher Frantz Fanon, who described ‘whiteness’ as at the apex of a white supremacist paradigm. In the west, ‘whiteness’ is constructed “as the symbol par excellence;” thus, ‘whiteness’ is not simply the pinnacle of superiority but the default, and something to which all ‘otherness’ is compared.[i] Postcolonialist and critical race theorist Sara Ahmed adds to this definition of ‘whiteness’ by explaining how it is “an ongoing and unfinished history, which orientates bodies in specific directions, affecting how they ‘take up’ space, and what they ‘can do’.”[ii] So what does this all mean for The Bright Ages?

The Bright Ages begins and ends in Ravenna, Italy, making thematic treks across lands and time. The central focus is the Holy Roman Empire with to episodes in Britain, France, Scandinavia, Iceland, the Iberian Peninsula, Germany, Jerusalem, Egypt, and a brief detour to central Asia and China. The book is peppered with passing references to other places, particularly North America, with mentions of Inuit and other Indigenous cultures. While the book recognizes the existence of Indigenous peoples, it also reinforces the idea that they exist on the periphery of European history. The core theme that runs through The Bright Ages is a Christocentric (that which is focused on Christ and Christian narratives) one that recycles the usual stories of emperors, bishops, kings, military leaders. Gabriele and Perry try to retell narratives about many conventional figures by discussing how outside influences and “otherness” played into their successes and failures.

Chapter 4, in part, focuses on the late 6th- and early 7th-century Pope, Gregory the Great (48) and explores how Christianity wasn’t (or isn’t) a monolith (50–53). The chapter then turns attention to Gregory’s Lombard ally, Queen Theodelinda (c. 570–628). Theodelinda, like women in subsequent chapters, is mentioned to exemplify how “queens were often the tip of the spear in Christian conversion efforts in this period” (53). Women who operated as Christian imperialists aren’t the progressive symbols that this book suggests. Gabriele and Perry exclaim that, although she meets an unhappy demise, “Theodelinda matters” (54). I hope this is not a play on Black Lives Matters, but it shows how I, as a Black reader and scholar, might encounter a particular phrase that (especially now) feels trivializing or appropriative.

Gabriele and Perry reveal their core audience through words and phrases that most likely would not raise the collective eyebrow of a predominantly white audience. We can’t change our positionality, but the book would have benefited from an acknowledgement that the author’ readings and interpretations came from their position as white males. Writing a book that aims to feature women and/or other marginalized figures demands a stepping outside of oneself that this work does not accomplish. Simply naming women who remained subsidiaries in a patriarchal society, or referring to auxiliary figures who were Muslim, Jewish, Mongols, or pagans (nevermind the erasure of trans or queer folk) in order to demonstrate how Christianity developed is nothing less than Christian apologia.

The book’s diction and phrasing signal its ‘white-centricism’ throughout. Not all audiences would associate “coconuts, ginger, and parrots” (xii) with “otherness.” Gabriele and Perry explain that “we mark the brown skin on the faces of the North Africans who always lived in Britain” (xii) juxtaposed with the “French Mediterranean peasants telling dirty stories about horny priests, raunchy women, and easily fooled husbands” (xii). They never mark white skin. Why is this so? In another place, they describe the Abrahamic religions as ‘south-west Asian’ while referencing Jesus himself as a “Jewish refugee from the eastern Mediterranean who once crossed into Africa, who had now come to this island where He sat comfortably” (74). While it is true that western religions have origins outside of Europe, descriptions like this try to de-Christianize Christianity, making it seem ‘hip,’ international and inclusive, while erasing its present role in western imperialism. At times, The Bright Ages goes to lengths to over-emphasize “otherness” in an attempt to normalize it, as though somehow describing Jesus in a way that medieval Christians would never have described him serves to appeal to a more liberal sensibility. The fact that the authors capitalize Jesus’ pronoun “He” suggests that they are playing to both a traditional audience and a seemingly progressive one.

As experts on the medieval Crusades, Gabriele and Perry are well informed about how white supremacists misappropriate medieval events, themes, and imagery. In several chapters, and in the epilogue, they reference how fascists and neo-Nazis have weaponized the Middle Ages. The Bright Ages challenges some racist and fascist notions (for example chapters 5, 7, 8, 10 and the epilogue point to a less white Europe ); however, Europe, Christianity, and whiteness remain central themes of the book. Further to this, there is nothing new about rehashing core texts beloved by white supremacists (particularly chapters 4, 5 and 7). The book is not under-researched, but it does play on a white male authority, especially in attempts to highlight difference and otherness. Gabriele and Perry are exceptional Crusader scholars but they rely on their whiteness for authority, as illustrated by how their 250+-page book has no footnotes or endnotes. What Gabriele and Perry demonstrate here as white, male historians is repeated in academia on a large scale. It’s an unspoken white entitlement and authority that masquerades as progressive, in which history is only validated through the lens and voices of white men.

This lack of substantial evidence is reinforced by a comparison to a book that achieves exactly what The Bright Ages does not. Historian Olivette Otele’s African Europeans: An Untold Story explores continued African presence throughout European history over millennia. Otele accomplishes here what Gabriele and Perry attempt, but the difference is she gives way to experts, engages with their work and effortlessly borrows from and weaves other scholarship into her own story-telling. Her work is grounded in evidence to reveal a history of Europe that is not white-washed. She makes her work accessible and readable, balancing her own voice with others as she shifts between being both an authority and a collaborator, quoting and footnoting other experts when necessary to strengthen her arguments and scholarship. Even after winning numerous awards, Otele continues to be critiqued for not having been rigorous enough. The Bright Ages, by contrast, weaponizes ‘whiteness’ as an unquestionable authority lacking in meticulousness and attention to detail demanded from marginalized scholars and/or women.

Focusing on beloved canonical texts seems somewhat counter-productive to any aims to deflate white supremacists. There have been a number of scholars over the last decade, for example, who have breathed new life into the Old English poem Beowulf by reshifting focus away from traditional readings. The Bright Ages, however, focuses exclusively on the two main women in Beowulf and offers a white feminist reading about power and powerlessness. There is a consistent pandering to a white feminist audience in this book. I agree with the authors that this work is necessary but it can’t be done hastily nor slapdash.

This book is invested in dispelling misconceptions of the term the ‘dark ages,’ but is that the myth that needs to be busted right now? Medievalists for decades now have long disrupted the notion of the “dark ages.” See for instance: here, here, and here. In public discourse now, if the term appears, it is met with fervent opposition, often on a personal level from medievalists (myself included) as a reactionary impulse to want to prove that the period is misunderstood and/or dangerously romanticized. Although correctives are important, medieval studies is struggling to grapple with problems of racism, sexism, homophobia, gatekeeping, and elitism, so one wonders why there would be an urgency to publish a book tackling the “dark ages” myth, since the authors reveal that “something significant has changed in how we think about the past just in the past few years” (257, 277–8).

A striking oversight in this book from start to finish is the erasure of scholars who brought this type of “rethinking the past” to light several generations ago. Scholars like Anna J. Cooper, W.E.B Du Bois, Gordon D. Houston, Jacqueline de Weever, Margo Hendricks, Ania Loomba, and Kim F. Hall. have laid the foundation for those who have written more recently about premodern critical race studies (PMCRS). What we see here is repackaged ‘whiteness.’ Gabriele and Perry state that multidimensional features of the medieval period connecting it to the present have remained in the dark “until now [as] those lights have often been hidden under a bushel of bad history” (xv). This not only contradicts the statement in their acknowledgements (255–6) and suggested further readings (257–78) where they say this work has been done before, but ignores the work of mostly marginalized scholars who laid the foundation for this book. Repurposing and reimagining that the field itself has not contended with issues for decades signals to an obliviousness that comes with the privilege of a white lens.

There is a lot of classic scholarship missing, which falsely gives readers the impression that premodernists have only been discussing and benefiting from PMCRS for the last five years. This is an indictment of The Bright Ages for drawing on the scholarship of scholars (especially Black ones) who have been doing this work for generations but have been all but erased in this monograph. Gabriele and Perry are right to mention works like Matthew X. Vernon’s The Black Middle Ages, but they seem to collapse Vernon’s thorough transhistorical examination of 19th-century uses of medieval texts to construct racial identity (particularly around the ‘Anglo-Saxon’ myth). The book’s clumsy and convoluted final sentences draw on two of the only Black scholars (Vernon and Cord Whitaker) in medieval studies to validate The Bright Ages as offering something new and to offset Gabriele’s and Perry’s identities as white men. The Bright Ages not only erases how Britain’s entire global enterprise of violent imperialism was rooted in an “Anglo-Saxon myth,” it misrepresents Vernon’s analysis of how African Americans utilized the Middle Ages: not simply to say the period belongs to us Black scholars, but that the west has centered their entire identity on a false sense of European greatness. This book reinforces that European ‘greatness’ rather than disrupting and decentering it. Name-dropping the most recognizable recent scholars of color in the field without engaging with previous scholars, particularly Black scholars in PMCRS further exemplifies a type of superficial value that scholars of color carry for white scholars. This, in turn, is reflected in cursory analyses where names of ‘others’ are only useful when they support white-centered narratives. Benefiting from marginalized scholars’ scholarship (without honoring their legacy) does a disservice to the field, erases the labor of scholarly forebears, and perpetuates the same problems the field continues to struggle with.

One of the most confusing and unsettling subjects in The Bright Ages is its focus on slavery, particularly in the Viking Era (100). Literary historian Kathleen Davis’ Periodization and Sovereignty discusses how scholars invented the idea “Dark Ages” as a time marked by slavery and violence. Not only does The Bright Ages not challenge those notions, it cheapens discussions of chattel slavery and undermines discussion of the transatlantic slave trade. The book’s epilogue stresses how “although chattel slavery — the buying and selling of humans — was more common in urbanized Mediterranean than elsewhere, a factor of easier access to markets, the principle of buying and selling humans was known to medieval people, just as to ancients, just as to moderns” (247). The book suggests that medieval slavery was no different than modern slavery, minimizing the horrors and anti-Blackness of the transatlantic slave trade where millions of Africans were dehumanized and enslaved. This book (presumably unintentional) echoes an unsettling anti-Blackness in the field partly because slavery is discussed in such a brief and fragmentary manner. It does a disservice to historians working on modern slavery and to Black and Brown people who are descendants of enslaved people. Revealing that Europe was not all white is important, but Europe need not continue to be centered. Crucially, there needs to be more mindful analyses of anti-Black discourse appearing in scholarly discourse around ‘diversity.’

The Bright Ages may not exclusively be for white readers, but it certainly is for neoliberal readers who want to believe they are progressive and demand superficial fixes to complex problems and issues. For what it’s worth, I don’t think there’s any illusion that the book aims to convert white supremacists, nor would any book really be able to achieve that. Still, it’s a safe book for a receptive liberal audience. It’s not radical, but that must be accepted at this moment, because the field is not ready for anything particularly radical. This book has value and is worth reading but with a critical eye. At its core, The Bright Ages is a carefully constructed narrative published at a time when predominantly white scholars and readers are eager to become recognized as “antiracist” (meaning one who actively works against white supremacy).

In my reading of this book, I discovered the “our” in “our story.” It gestures to a (mostly) white, neoliberal reader who will buy a book about “diversity” in the Middle Ages without questioning why two white male scholars are capitalizing on race and otherness for profit. To be ‘othered’ is to be subject to the shifting needs and desires of capitalism. This is what political scientist Cedric Robinson refers to as “racial capital.” The Bright Ages commodifies and repackages Brown, Black, and other marginalized figures to sell “diversity” to an eager audience 6wawho will overlook recycled whiteness. Rather than showing the brightness of the Middle Ages, The Bright Ages simply repackages whiteness.

[i] Frantz Fanon. Black Skin, White Masks. New York: Grove Press, 1958/2008: xii

[ii] Sara Ahmed. “A phenomenology of whiteness,” Feminist Theory, 8.2 (2007), 149–168, at 149.